Writing a book is hard. I’ve written seven books and at some point during each one I had the thought, “There has to be a tool, a piece of book writing software, that would make this easier.”

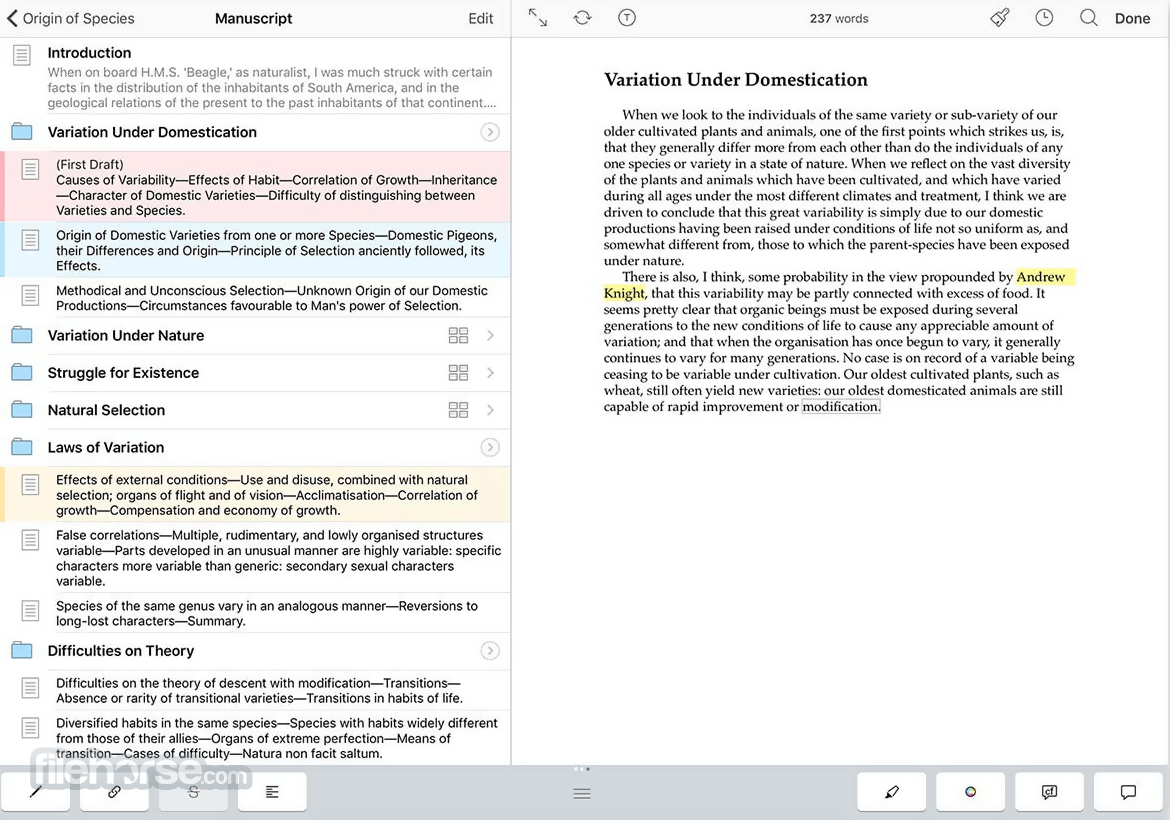

The best writing software overall is: Scrivener Scrivener is packed with all the features a novelist needs, helping you track plot threads, store notes on characters and locations, structure your. Scrivener is the ultimate book-organization tool. It allows you to view your notes.

Bad news/good news: writing a book will always be hard, and the best piece of writing software in the world won’t write your book for you. But the good news is there is book writing software that can make the process a little easier.

In this post, we will cover the ten best pieces of software for writing a book and look at the pros and cons of each.

Click the links below to get our review on the best writing software.

Best Writing Software: Contents

Worst Pieces of Software for Writing a Book

First, though, let’s cover software you should avoid, at least while you’re writing a book:

- Video Games. Especially World of Warcraft (always always always!) but also Solitaire, Sudoku, Angry Birds, and, for me right now, Star Wars Galaxy of Heroes.

- Facebook, Twitter, and Other Social Media Software. Do I really need to say more? Fortunately there’s a piece of book writing software for avoiding this very distracting software (see Freedom below).

- Other Productive Software Not Directly Associated With Your Writing. Yes, it’s good to reconcile your bank account on Quickbooks or make sure you’re up to date on your calendar app, but responsible, well-meaning work can easily be an excuse for a quick distraction that turns into a major distraction from writing your book.

Set aside time for your writing every day and then stay focused!

If you need a game, make writing your daily word count your game.

If you want more “likes” on social media, imagine how great getting five-star reviews on your book will be.

If you need to check your bank balance several times a day, think about what your bank balance will be when you stop checking it constantly, finish your book, and become a successful author.

The 10 Best Pieces of Book Writing Software

No piece of writing software will write your book for you, but these ten will help. Let’s look at the pros and cons of each.

1. Scrivener (Word Processor)

Scrivener is the premier book writing software. It is made by writers for writers. Scrivener’s “binder” view allows you to break up your book into chapters and sections and easily reorganize it. Project targets let you create word count goals and then track your progress daily. Its composition mode can help you stay focused by removing all the clutter. Plus, it allows you to format for publishing (e.g. on Amazon or Barnes & Noble).

There are some problems with Scrivener. Formatting is more complicated than it needs to be and collaborating isn’t easy, meaning it loses its effectiveness as soon as you bring on an editor. But it more than makes up for that by being so helpful in the early stages of the writing process.

In fact, we believe in Scrivener so much, we published a book about how creative writers can write more, faster using it. It’s called Scrivener Superpowers. If you’re using Scrivener or want to save yourself time as you learn how to use it for your creative writing, you can get Scrivener Superpowers here. The next edition comes out on Tuesday!

Cost: $49 for Mac, $45 for Windows

You can get a copy of Scrivener here, or learn more about how to use the software with one of these resources:

- Scrivener Superpowers by M.G. Herron

2. Google Docs (Word Processor)

While Scrivener is the best book writing software, once you get to editing and getting feedback, it begins to fall short.

That’s why Google Docs has become my second go-to piece of book writing software. It’s free, very easy to use, and requires no backups since everything is in the cloud.

Best of all are its collaboration abilities, which allow you to invite your editor to the document and then watch as he or she makes changes, tracked in suggestion mode, and leave comments on your story (see screenshot below).

Cost: Free!

3. Google Sheets (Spreadsheet)

If you’d told me when I was first trying to become a writer that one of my most-used tools in my book writing software toolkit would be a spreadsheet, I would have told you I didn’t major in English to have to use a spreadsheet.

But now, as I’m finishing my twelth book, I realize that I’m using spreadsheets almost daily.

Spreadsheets allow you to get a sense of the elements of your book at a glance, and when you’re working on a 300-page document, distilling it down to useable information becomes very necessary.

You might use spreadsheets for:

- Character tracking

- Scene lists

- Outlines

Google Sheets is perfect for this because it’s free and you can quickly share your documents with your writing partners, editors, or beta readers to get feedback. Microsoft Excel is another great option, but for writers, I suggest Google Sheets.

Cost: Free!

4. Vellum (Book Formatting/Word Processor)

If you want to turn your book into an eBook, it’s not that hard. Scrivener, Word, Pages, they all can make eBooks. But that doesn’t mean they’ll look good. In fact, it takes a lot of skill and effort to make an eBook look good on any of those word processors. That’s why I love Vellum so much.

Vellum makes beautiful eBooks.

Vellum picks up where Scrivener, Word, and Pages leave off, giving you a tool to make great looking eBooks every time.

The most important part of this is the previewer (see the image below), which lets you see how each formatting change or book edit you make will appear on Kindle, Fire, iPhone, Nook, and other eReaders.

It also has stripped-down, option-based formatting, which is perfect for designing eBooks.

I really love this app!

UPDATE: Vellum recently expanded into formatting for paperback books! I haven’t tried it yet but it looks awesome!

Cost: $199 for eBook generation, $249 for Paperback Formatting

5. Freedom (Productivity App)

One question writers always ask me is, “How can I stay focused enough to finish what I write?”

I have too many thoughts on this for this article, but as far as writing software to encourage focus, I recommend Freedom.

Freedom allows you to block your biggest distractions online, including both websites and mobile apps, for a set period of time. So when you mindlessly escape your book to scroll through Facebook, you’ll find the site won’t load.

You can also schedule recurring sessions, so that at a scheduled time (e.g. Mondays from 6 am to 10 am), you won’t be able to access the sites on your blocklist, even if you try.

There are other apps like this that we’ve written about before, notably Self-Control for Mac and StayFocused for Windows. But Freedom goes further, allowing you to block sites on both your computer and your phone, and enabling recurring sessions.

You can learn more about how writers can get the most out of Freedom on our review here.

Cost: $29 / year for Pro version, which I use and recommend (Free trial available)

6. Microsoft Word (Word Processor)

Again: no piece of book writing software is going to write your book for you. If you’re looking for the next “shiny new toy” to help you write your book, it might be an excuse to avoid doing the hard work of writing.

Most of us learned how to use computers by using Microsoft Word, or a program like it. Word gets the job done. Sure, Scrivener is a little better for books, but I wrote my first book on Word and it’s fine.

I wrote a long review of the pros and cons of using Word to write books—the main problem is that as your document grows, it becomes more and more difficult to work with, whereas with Scrivener, it becomes easier—but the point is, if Word is what you have, don’t let that stop you from finishing your book.

As Jeff Elkins said in his review of Word, “If you aren’t already putting in the hard work to be the kind of writer you want to be, it doesn’t matter what new writing software you invest in. It is not going to help.”

Cost: $69 / year from Amazon (includes Excel, Powerpoint, Outlook, and other Microsoft software)

7. Ulysses (Word Processor)

When I’m writing for a long time, I like to get up and go for a walk. Sometimes, I wish I could continue writing while I walk. Other times, I come up with an idea while I’m walking, type it up on my phone, and then want to easily move what I wrote to my laptop without having to go through the hassle of emailing it back and forth to myself.

That’s where Ulysses comes in.

Ulysses is a word processor for Mac that allows you to sync between all your devices, so you have what you need wherever you are. Scrivener recently released their iOS app which allows you to do this as well, but the process is clunky and requires you to purchase both the desktop and iOS apps. Ulysses’ sync makes the process much more seamless.

Write Programs In Machine Language

Like Scrivener, it has a binder-like sidebar that allows you to move documents around. Ulysses is not designed specifically for books so it takes a little configuring to make it work for you, but once you have it set up the way you want it’s very intuitive.

And while I hate Markdown, I actually like the paired-down formatting options Ulysses gives. Overall, I’m not going to convert from Scrivener to Ulysses any time soon, but I think it’s a great option for most writers.

Cost: $45

8. Microsoft Excel (Spreadsheets)

As Jeff Elkins says in his review of Microsoft Excel, it’s great, but “it’s a little like bringing a bazooka to a knife fight. You will need only a small fraction of its capability.”

If you have Excel and love it, great. Otherwise, use Google Sheets, especially if you’re sharing your sheet with a collaborator or editor.

Cost: $69 / year from Amazon (includes Word, Powerpoint, Outlook, and other Microsoft software)

9. ProWritingAid (Grammar/Spell Check)

Can book writing software replace an editor?

Definitely not. But if you ask Alice Sudlow, our in-house editor, she’s tell you, “If you don’t have access to an editor (or if you do, but you don’t want to hire them to edit your emails or Facebook posts), grammar checking software like ProWritingAid is an accessible, affordable alternative.

If you struggle with grammar, sentence structure, spelling, or even writing style, ProwritingAid can help. It goes far beyond your built-in spell-check.

You should still learn grammar skills, but ProWritingAid can help you start to see the patterns and grow as a writer.

There’s a free version that’s very good. It can even be installed into your browser or Word processor, so you can check your grammar wherever you write. The paid version, just $60 a year (less than half of what Grammarly costs), gives you additional support on sentence structure, style, and vocabulary.

Learn more about how writers can get the most out of ProWritingAid here.

Cost: Free! (Premium version is $60 / year)

10. Hemingway App (Grammar/Style Checker)

Most writers think their sentences are easier to read than they are. You think you’re coming across clearly, that your writing makes sense, but then someone reads it and comes away with something totally different.

Hemingway App helps with that.

Hemingway App is a free website that checks readability. You can copy and paste your writing into the website’s input box. Then it will grade your writing based on your used of adverbs, passive voice, and sentences as units.

Hemingway App is useful, but even the best book writing software can’t replace a good editor.

Cost: Free!

The 7 Tools Every Writer Needs

Every professional has a set of tools at their disposal that not only makes their job possible, but makes them better at doing it. Writing is no different, and while the right software is important, it’s just one of the many tools you need as a writer.

That’s why we published a free 22-page eBook, 7 Tools to Help You Write a Novel. In this short guide, we’ll cover some of the basic tools that form the foundation of a writing life.

You can download it for free here. Enjoy!

The Most Essential Book Writing Software

Imagine it’s three thousand years ago. You’re sitting around a campfire with some of your family and friends, tired from the day’s work. You begin to tell a story. It’s one you’ve told before, told a hundred times. You can see faces around the fire, the children with their eyes wide, the men and women who have heard the story before but still enjoy it because it brings meaning to their lives.

Storytellers—writers—have existed since the beginning of humanity. They didn’t always have book writing software. They didn’t have the printing press or the internet. They didn’t always even have the alphabet to write their stories down.

Instead, storytellers had their imaginations, their voices, and a rapt audience.

You don’t need book writing software to write a great story. Book writing software can make the process a little faster or easier, but the truth is great stories will always exist, no matter what kind of software we have.

The only three things essential to writing a great book:

- Your imagination

- Your words

- A desire to tell your story

That’s all you need. Do you want to write your book? If you do, then do it. Write it. Nothing is stopping you except you. So go get writing.

What pieces of book writing software do you use? Let us know in the comments.

PRACTICE

The world is full of powerful software to help you write your book. In the end, though, all these tools are just that—tools. The stories you imagine and your discipline to put the words on the page are far more important.

So for this practice, set aside all the fancy software. Eliminate all the bells and whistles and open up your computer’s native text editor (TextEdit for Mac or Notepad for Windows). Take fifteen minutes to write without any distractions. Continue your work in progress, or start a new story based on this prompt:

A student discovers one of their teachers is not what they appear to be.

When you’re done, share your writing practice in the comments. And if you share, be sure to leave feedback for your fellow writers!

Apps are the most common type of Mac software, but there are many other types of software that you can create, too. The following sections introduce the range of software products you can create for the Mac platform and suggest when you might consider doing so.

Apps

Apps are by far the predominant type of software created for Mac, or for any platform. You use Cocoa to build new Mac apps. To learn more about the features and frameworks available in Cocoa, see Cocoa Application Layer.

In general, there are three basic styles of Mac apps:

The single-window utility app. A single-window utility app helps users perform the primary task within one window. Although a single-window utility app might also open an additional window—such as a preferences window—the user remains focused on the main window. Calculator is an example of a single-window utility app.

The single-window “shoebox” app. The defining characteristic of a shoebox app is the way it gives users an app-specific view of their content. For example, iPhoto users don’t find or organize their photos in the Finder; instead, they manage their photo collections entirely within the app.

The multiwindow document-based app. A multiwindow document-based app, such as Pages, opens a new window for each document the user creates or views. This style of app does not need a main window (although it might open a preferences or other auxiliary window).

App Extensions

No matter what type of app you write, you use app extensions to extend the functionality and content of that app to other parts of the system, or even to other apps. Types of extensions include:

Today. Display information from your app, or perform a quick task in the Today view of Notification Center.

Share. Share information with others by posting information to a website or social service, or sending data out in some other way.

Action. Create a context allowing the user to manipulate or view items from your app inside another app.

Finder. Show the sync state information in Finder.

App Store

Regardless of the app style you choose, your goal is probably to get your app into the Mac App Store. The development process that helps you achieve this goal includes a mix of coding and administrative tasks.

This document gives you an overview of Mac technologies that you can incorporate into your app. To learn more about the other tasks involved in the development process, read App Distribution Quick Start.

Development Languages

The tools for OS X supports many different development languages. In addition to Swift, Objective-C, C++, C, and other such languages, Xcode provides support for many scripting languages. For more information, see Scripts below.

The most common languages used for development for OS X are Swift and Objective-C. The following sections call out key features in some of these environments.

Swift

Swift is a new programming language for Cocoa and Cocoa Touch with a concise and expressive syntax. Swift incorporates research on programming language combined with decades of experience building Apple platforms. Code written in Swift co-exists with existing classes written in Objective-C, allowing for easy adoption.

Some of the key features of Swift are:

Closures unified with function pointers

First class functions

Tuples and multiple return values

Generics

Fast and concise iteration over a range or collection

Structs and Enums that support methods, extensions, and protocols

Functional programming patterns

Type safety and type inference with restricted access to direct pointers

Swift also supports the use of Playgrounds, an interactive environment for real time evaluation of code. Use playgrounds for designing a new algorithm, creating and verifying new tests, or learning about the language and APIs.

To learn more about Swift, see The Swift Programming Language, or for a quick overview, see Welcome to Swift.

Objective-C

Objective-C is a C-based programming language with object-oriented extensions. It is a primary development language for Cocoa apps. Unlike C++ and some other object-oriented languages, Objective-C comes with its own dynamic runtime environment. This runtime environment makes it much easier to extend the behavior of code at runtime without having access to the original source.

Objective-C 2.0 supports the following features, among many others:

Blocks (which are described in Block Objects)

Declared properties, which offer a simple way to declare and implement an object’s accessor methods

A

foroperator syntax for performing fast enumerations of collectionsFormal and informal protocols, which allow you to declare methods that are independent of any specific class, but which any class might implement

Categories and extensions, both of which allow you to add methods to an existing class

To learn about the Objective-C language, see The Objective-C Programming Language.

Other Types of Software

There are many other types of software you can develop for Mac. Most of these software products have no user interface (UI) and instead provide services that extend the capabilities of other software, such as third-party apps or the system itself.

Utility Programs For Mac

Frameworks

A framework is a special type of bundle used to distribute shared resources, including library code, resource files, header files, and reference documentation. Frameworks offer a more flexible way to distribute shared code—for example, image files and localized strings—that you might otherwise put into a dynamic shared library. Frameworks also have a version control mechanism that makes it possible to distribute multiple versions of a framework in the same framework bundle.

Apple uses frameworks to distribute the public interfaces of OS X (and iOS), which are packaged in software development kits. A software development kit (SDK) collects the frameworks, header files, tools, and other resources necessary for developing software targeted at a specific version of a platform. You, too, can use frameworks to distribute public code and interfaces that you create, or to develop private shared libraries to embed in your apps.

Note: Although OS X also supports the concept of an “umbrella” framework, which encapsulates multiple subframeworks in a single package, this mechanism is used primarily for the distribution of Apple software. The creation of umbrella frameworks by third-party developers is not recommended.

You can use any programming language to create your own frameworks, but it’s best to choose a language that makes it easy to update the framework later. Apple frameworks generally export programmatic interfaces in ANSI C, Swift, or Objective-C. Both of these languages have a well-defined export structure that makes it easy to maintain compatibility between different revisions of the framework.

To learn about the structure and composition of frameworks, see Framework Programming Guide. That document also describes how to use Xcode to create public and private frameworks.

Plug-ins

Plug-ins are the standard way to extend many apps and system behaviors. A plug-in is a bundle whose code is loaded dynamically into the runtime of an app. Because it’s loaded dynamically, a plug-in can be added and removed by the user.

The app and system plug-ins listed below represent some of the many opportunities for developing plug-ins.

Address Book action plug-ins. An Address Book plug-in lets you add custom actions that act on the data in a person’s Address Book card. For example, the existing Large Type action displays the selected phone number in large type. Each action plug-in performs a single action, which can open a simple window within the Address Book app. If an action needs to do anything else, it must launch your app to perform the action. To learn how to create an Address Book action plug-in, see Creating and Using Address Book Action Plug-ins.

App plug-ins. An app plug-in can extend the features of any app that supports a plug-in model. In addition to third-party apps, several Apple apps also support plug-ins, such as iTunes, Final Cut Pro, and Aperture. For information about developing plug-ins for Apple apps, visit the Apple Developer website.

Automator plug-ins. Using an Automator plug-in, you can expand the default set of actions available in Automator, a utility app that lets users assemble complex scripts using a palette of predefined actions. Automator plug-ins can be written in AppleScript or Objective-C, so you can write them for your own app’s features or for the features of other scriptable apps. (It’s a good idea to provide Automator plug-ins for your app’s most common tasks because doing so gives users more ways to interact with your app.) To learn how to write an Automator plug-in, see Automator Programming Guide.

Core Audio plug-ins. A Core Audio plug-in can support the manipulation of audio streams during most processing stages. For example, you can use plug-ins to generate, process, or receive an audio stream or to interact with new types of audio-related hardware devices. To begin learning about Core Audio, read Core Audio Overview.

Image units. An image unit is a type of plug-in that you can use with the Core Image and Core Video technologies. An image unit consists of a collection of filters—each of which implements a specific manipulation for image data—packaged together in a single bundle. For example, you could write a set of filters that perform different kinds of edge detection and package them as one image unit. To learn how to create an image unit, see Creating Custom Filters.

Adobe photoshop elements 2019 mac download. Input methods. A common example of an input method is an interface for typing Japanese or Chinese characters using multiple keystrokes. Other examples of input methods include spelling checkers and pen-based gesture recognition systems. You can create input methods using Input Method Kit (InputMethodKit.framework). For information on how to use this framework, see Input Method Kit Framework Reference.

Metadata importers. Spotlight relies on metadata importers to gather information about the user’s files and to build a systemwide index. Spotlight uses this index to help users find information by searching on attributes that make sense to them, such as the duration of a video or the dimensions of an image. If your app defines a custom file format, you should always provide a metadata importer for that file format. (If your app relies on commonly used file formats, such as JPEG, RTF, or PDF, the system provides a metadata importer for you.) To learn how to create metadata importers, see Spotlight Importer Programming Guide.

Quartz Composer plug-ins. Quartz Composer supports a plug-in mechanism that allows you to create a custom patch and make it available in the Quartz Composer workspace and to most Quartz Composer clients. (A patch is processing unit that performs a specific task, such as processing a string or rendering an OpenGL texture.) To learn how to create a Quartz Composer plug-in, see Quartz Composer Custom Patch Programming Guide.

Quick Look plug-ins. A Quick Look plug-in—also known as a Quick Look generator—converts a document from its native format into a format that Quick Look can display to users. If your app creates documents of a nonstandard or private type, it’s a good idea to provide a Quick Look generator so that users can get previews of these documents in Quick Look. To learn how to create a Quick Look plug-in, see Quick Look Programming Guide.

Safari plug-ins. Safari supports the Netscape-style plug-in model for incorporating additional types of content in the web browser. In Safari in OS X v10.7 and later, these plug-ins run in their own process, which improves the stability and security of Safari. Netscape-style plug-ins include support for onscreen drawing, event handling, and networking and scripting functions.

Note: Beginning in OS X v10.7, Safari does not support WebKit plug-ins because they are not compatible with the new process architecture. Going forward, you must convert WebKit plug-ins to Netscape-style plug-ins or Safari Extensions.

For information about creating Safari plug-ins with the Netscape API, see WebKit Plug-In Programming Topics and WebKit Objective-C Framework Reference.

Safari Extensions

Use Safari extensions to add features both to the Safari web browser and to the content that Safari displays. For example, you can add custom buttons to the browser’s toolbar, reformat webpages, block unwanted sites, and create contextual menu items. Extensions let you inject scripts and style sheets into pages of web content.

A Safari extension is a collection of HTML, JavaScript, and CSS files with support for both HTML5 and CSS3. Safari extensions are supported in both OS X and Windows systems running Safari 5.0 and later.

To learn more about Safari extensions, read Safari Extensions Development Guide in the Safari Developer Library.

Agent Applications

An agent is a special type of application that typically runs in the background, providing information as needed to the user or to another app. For example, the Dock is an agent application that is run by OS X.

An agent can be launched by the user but is more likely to be launched by the system or another app. As a result, agents do not show up in the Dock or the window displayed by the Force Quit menu command. Although agents might occasionally come to the foreground and display a user interface, they do not have a menu bar for choosing commands. All user interaction with an agent application is brief and focused on a specific goal, such as setting preferences or requesting information.

To create an agent application, you create a bundled app and include the LSUIElement key in its information property list (Info.plist) file. For more information on using this key, see Information Property List Key Reference.

Screen Savers

Screen savers are small programs that take over the screen after a certain period of idleness. Screen savers provide entertainment and also prevent the screen image from being burned into the surface of a display. OS X supports both slideshows and programmatically generated screen-saver content.

A slideshow is a simple type of screen saver that does not require any code to implement. To create a slideshow, you create a bundle with an extension of .slideSaver. Inside this bundle, you place a Resources directory that contains the images you want to display in your slideshow. Your bundle should also include an information property list that specifies basic information about the bundle, such as its name, identifier string, and version.

OS X includes several slideshow screen savers you can use as templates for creating your own. These screen savers are located in /System/Library/Screen Savers. You should put your own slideshows in either /Library/Screen Savers or in the ~/Library/Screen Savers directory of a user.

A programmatic screen saver is a screen saver that continuously generates content to appear on the screen. You can use this type of screen saver to create animations or to create a screen saver with user-configurable options. The bundle for a programmatic screen saver ends with the .saver extension.

You create programmatic screen savers using Cocoa with the Swift language or with Objective-C. Specifically, you create a custom subclass of ScreenSaverView that provides the interface for displaying the screen saver content and options. The information property list of your bundle provides the system with the name of your custom subclass. For information on creating programmatic screen savers, see Screen Saver Framework Reference.

Services

Services are not separate programs that you write; instead, they are features exported by your app for the benefit of other apps. Services let you share the resources and capabilities of your app with other apps in the system. Users access services through the Services menu that is available in every app’s application menu. (Services replace the contextual menu plug-in functionality that was available in earlier versions of OS X.)

A service typically acts on the currently selected data. When the user initiates a service, the app that holds the selected data places it on the pasteboard. The app whose service was selected then takes the data, processes it, and puts the results (if any) back on the pasteboard for the original app to retrieve. For example, a user might select a folder in the Finder and choose a service that compresses the folder contents and replaces them with the compressed version. Services can represent one-way actions as well. For example, a service could take the currently selected text in a window and use it to create the content of a new email message. For information on how to provide and use services in your app, see Services Implementation Guide.

Preference Panes

Preference panes are used primarily to modify system preferences for the current user. Preference panes are implemented as plug-ins and installed in /Library/PreferencePanes. App developers can also take advantage of these plug-ins to manage per-user app preferences; however, most apps provide their own UI to manage preferences.

You might need to create preference panes if you create:

Hardware devices that are user configurable

Systemwide utilities, such as virus protection programs, that require user configuration

If you're an app developer, you might want to reuse preference panes intended for the System Preferences app or use the same model to implement your app preferences. To learn how to create and manage preference panes, read Preference Pane Programming Guide.

Dynamic Websites and Web Services

OS X supports a variety of techniques and technologies for creating web content. In addition to Identity Services, dynamic websites and web services offer web developers ways to deliver their content quickly and easily.

OS X provides support for creating and testing dynamic content in web pages. If you are developing CGI-based web apps, you can create websites using a variety of scripting technologies, including Perl and the PHP Hypertext Preprocessor (a complete list of scripting technologies is provided in Scripts). You can also create and deploy more complex web apps using JBoss, Tomcat, and WebObjects. To deploy your webpages, use the built-in Apache HTTP web server.

Safari provides standards-compliant support for viewing pages that incorporate numerous technologies, including HTML, XML, XHTML, DOM, CSS, Java, and JavaScript. You can also use Safari to test pages that contain multimedia content created for QuickTime, Flash, and Shockwave.

The Simple Object Access Protocol (SOAP) is an object-oriented protocol that defines a way for programs to communicate over a network. XML-RPC is a protocol for performing remote procedure calls between programs. In OS X, you can create clients that use these protocols to gather information from web services across the Internet. To create these clients, you use technologies such as PHP, JavaScript, AppleScript, and Cocoa.

Representational State Transfer (REST) is an alternative method for transferring data using URLs. OS X provides full support for building REST applications through NSURL, NSURLSession, and related classes. For more information, see URL Loading System Programming Guide.

If you want to provide your own web services in OS X, use WebObjects or implement the service using the scripting language of your choice. You then post your script code to a web server, give clients a URL, and publish the message format your script supports.

For information on how to create client programs using AppleScript, see XML-RPC and SOAP Programming Guide. For information on how to create web services, see WebObjects Web Services Programming Guide.

Mail Stationery

The Mail app provides templates that give users prebuilt email messages that are easily customized. Because templates are HTML based, they can incorporate images and advanced formatting to give the user’s email a much more stylish and sophisticated appearance.

Developers and web designers can create custom template packages for external or internal users. Each template consists of an HTML page, a property list file, and a set of images which are packaged together in a bundle and then stored in the Mail app’s stationery folder. The HTML page and images define the content of the email message and can include drop zones for custom user content. The property list file gives Mail information about the template, such as its name, ID, and the name of its thumbnail image. To learn how to create new stationery templates, see Mail Programming Topics.

Command-Line Tools

Command-line tools are simple programs that manipulate data through a text-based interface. These tools do not use windows, menus, or other user interface elements traditionally associated with apps. Instead, they run from the command-line environment of the Terminal app. Because command-line tools require less explicit knowledge of the system to develop, they are often simpler to write than many other types of software. However, command-line tools are best suited to technically savvy users who are familiar with the conventions and syntax of the command-line interface.

Xcode supports the creation of command-line tools from several initial code bases. For example, you can create a simple and portable tool using standard C or C++ library calls, or you can create a tool more specific to OS X using frameworks such as Core Foundation, Core Services, or Cocoa Foundation.

Launch Items and Daemons

Launch items are special programs that launch other programs or perform one-time operations during startup and login periods. Daemons are programs that run continuously and act as servers for processing client requests. You typically use launch items to launch daemons or perform periodic maintenance tasks, such as checking the hard drive for corrupted information.

Launch items should not be confused with the login items found in the Accounts system preferences. Login items are typically agent applications that run within a given user’s session and can be configured by that user. Launch items are not user-configurable.

Few developers should ever need to create launch items or daemons. These programs are reserved for special situations in which you need to guarantee the availability of a particular service. For example, OS X provides a launch item to run the DNS daemon. Similarly, a virus-detection program might install a launch item to launch a daemon that monitors the system for virus-like activity. In both cases, the launch item would run its daemon in the root session, which provides services to all users of the system. To learn more about launch items and daemons, see Daemons and Services Programming Guide.

Scripts

A script is a set of text commands that are interpreted at runtime and turned into a sequence of actions. Most scripting languages provide high-level features that make it easy to implement complex workflows quickly. Scripting languages are often very flexible, letting you call other programs and manipulate the data they return. Some scripting languages are also portable across platforms, so that you can use your scripts anywhere.

Table 1-1 lists many of the scripting languages available in OS X.

Language | Description |

|---|---|

AppleScript | An English-based language for controlling scriptable apps in OS X. Use it to tie together apps involved in a custom workflow or repetitive job. For more information, see AppleScript Overview. |

| A Bourne-compatible shell script language used to build programs on UNIX-based systems. |

| The C shell script language used to build programs on UNIX-based systems. |

Perl | A general-purpose scripting language supported on many platforms. Perl provides an extensive set of features suited for text parsing and pattern matching and also has some object-oriented features. For more information, see The Perl Programming Language website. |

PHP | A cross-platform, general-purpose scripting language that is especially suited for web development. For more information, see PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor. |

Python | A general-purpose, object-oriented scripting language implemented for many platforms. For more information, see Python Programming Language. To learn about using Python with the Cocoa scripting bridge, see Ruby and Python Programming Topics for Mac. |

Ruby | A general-purpose, object-oriented scripting language implemented for many platforms. For more information, see Ruby Programming Language. To learn about using Ruby with the Cocoa scripting bridge, see Ruby and Python Programming Topics for Mac. |

| The Bourne shell script language used to build programs on UNIX-based systems. |

Swift | Use the command line Swift compiler to create scripts. For information on the Swift command line tool type |

Tcl | A general-purpose language implemented for many platforms. Tcl (Tool Command Language) is often used to create graphical interfaces for scripts. For more information, see Tcl Developer Site. |

| A variant of the C shell script language used to build programs on UNIX-based systems. |

| The Z shell script language used to build programs on UNIX-based systems. |

Scripting Additions for AppleScript

A scripting addition delivers additional functionality for AppleScript scripts by adding systemwide support for new commands or data types. Developers who need features not available in the current command set can use scripting additions to implement those features and make them available to all apps. For example, one of the built-in scripting additions extends the basic file-handling commands to support the reading and writing of file contents from an AppleScript script. For information on how to create a scripting addition, see Technical Note TN1164, “Scripting Additions for OS X.”

Kernel Extensions

Kernel extensions are code modules that load directly into the kernel process space and therefore bypass the protections offered by the OS X core environment. Most developers have little need to create kernel extensions. The situations in which you might need a kernel extension are the following:

Your code needs to handle a primary hardware interrupt.

The client of your code is inside the kernel.

A large number of apps require a resource your code provides. For example, you might implement a file-system stack using a kernel extension.

Your code has special requirements or needs to access kernel interfaces that are not available in the user space.

Although a device driver is a type of kernel extension, by convention the term kernel extension refers to a code module that implements a new network stack or file system. You would not use a kernel extension to communicate with an external device such as a digital camera or a printer. (For information on communicating with external devices, see Device Drivers.)

Best Writing Programs Mac

Note: Kernel data structures have an access model that makes it possible to write nonfragile kernel extensions—that is, kernel extensions that do not break when the kernel data structures change. Developers are highly encouraged to use the kernel-extension API for accessing kernel data structures.

Developing a kernel extension must be signed by a special type of developer ID certificate. Paid members of the developer program can request a kernel signing ID at https://developer.apple.com/contact/kext/.

For information about writing kernel extensions, see Kernel Programming Guide.

Device Drivers

Device drivers are a special type of kernel extension that enable OS X to communicate with many hardware devices, including mice, keyboards, and FireWire drives. Device drivers communicate hardware status to the system and facilitate the transfer of device-specific data to and from the hardware. OS X provides default drivers for many types of devices, but these might not meet the needs of all hardware developers.

Although developers of mice and keyboards might be able to use the standard drivers, many other developers require custom drivers. Developers of hardware such as scanners, printers, AGP cards, and PCI cards typically have to create custom device drivers because these devices require more sophisticated data handling than is usually needed for mice and keyboards. Hardware developers also tend to differentiate their hardware by adding custom features and behavior, which makes it difficult for Apple to provide generic drivers to handle all devices.

Writing Programs For Mac Free

Apple provides code you can use as the basis for your custom drivers. The I/O Kit provides an object-oriented framework for developing device drivers using C++. To learn more about the I/O Kit, see IOKit Fundamentals.

Writing Programs For Mac

Who Helped Babbage Write Programs For His Machines

Copyright © 2004, 2015 Apple Inc. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Updated: 2015-09-16